This is Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality—my attempt to make myself, and all of you out there in SubStackLand, smarter by writing where I have Value Above Replacement and shutting up where I do not… What Happened with Elon Musk & the "CyberTruck", Anyway?EV freedom vs. bunker aesthetics: how the Cybertruck squandered the skateboard, and misfired as its stainless shell met actual materials-science physics. A bold silhouette, a brittle reality: the...EV freedom vs. bunker aesthetics: how the Cybertruck squandered the skateboard, and misfired as its stainless shell met actual materials-science physics. A bold silhouette, a brittle reality: the CyberTruck as anti-humanist sculpture…EV skateboards enable airy, efficient cabins, yet the Cybertruck chose bunker aesthetics and hostile apertures. It denies utility, comfort, and scale economics. Its success depended on creating a new tribe—call them the lovers of while demanding a new tribe to forgive the trade-offs. But it turned out that the original Tesla market segment of rich techbros who wanted to pledge allegiance to an electric and green future did not want the techno‑sovereign Mad Max post‑apocalyptic vibe of the CyberTruck, and with Musk’s kleptofascist political turn it turned out that the market for Dukes-of-Hazzard-themed CyberTrucks was very limited. And now we are approaching the denouement:

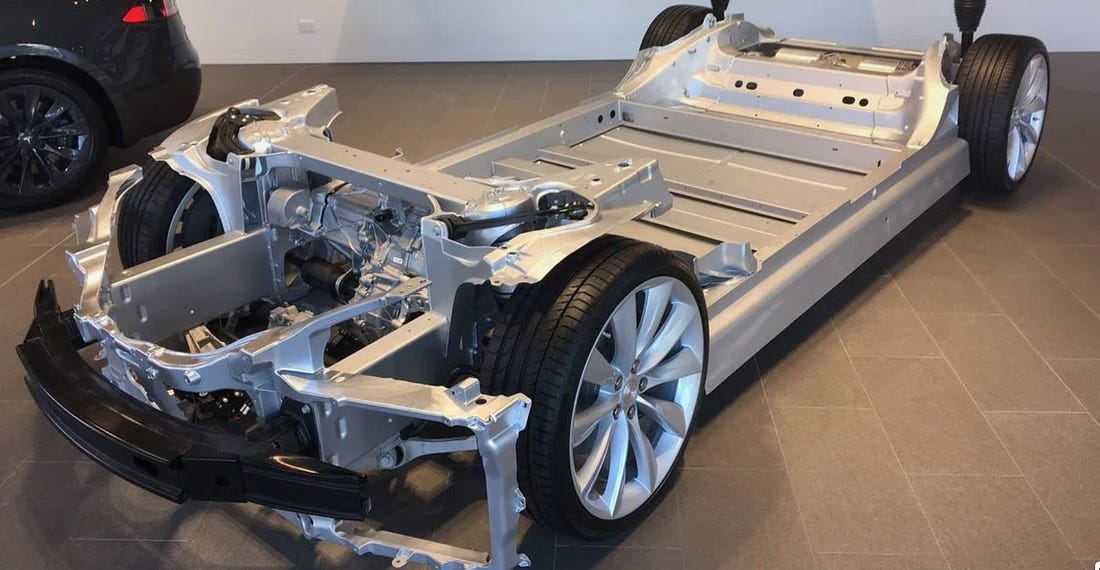

An electric vehicle is—or can be—a skateboard: a flat, self-contained chassis that houses the battery, motors, thermal management, crash structures, and control electronics, upon which you bolt a “top‑hat” of nearly any shape. That modularity has mattered for both engineering economics and product variety since the early 2000s, when GM’s AUTOnomy/Hy‑Wire experiments showed proof that propulsion and energy storage belong in the floor. The modern execution is everywhere: Tesla S/3/X/Y, Rivian’s quad‑motor “adventure”, Volkswagen’s MEB for the ID. family: Consider our VW ID.BUZZ: Take the skateboard’s flat floor and low center of gravity, then drop a faithful 1960s MicroBus “top‑hat” on it: Suddenly you have: maximal cubic volume for people and stuff, easy ingress and egress, and sightlines that feel more living room than cockpit. It’s a nostalgia aesthetic doing real work: The retro form factor isn’t just charming. It’s packaging‑efficient. And in Berkeley it doubles as social signaling: less “tech‑bro brutalism,” more “community‑minded practicality”, plus it makes us the object of great envy on the part of all of our 70‑something onetime-hippie or hippie-want-to-have-been neighbors. So why, given all that design freedom, would you sculpt a vehicle into a maze of cramped corners and overhangs—functionally hostile, aerodynamically mediocre—and then finish it with the visual vocabulary of a dumpster? Most EV makers, and the earlier Tesla, used that freedom to produce swoopy forms with good aero, pleasant sightlines, and cabins that feel like rooms, not bunkers. Tesla, with the Cybertruck, chose instead a low-resolution triangle: severe planar stainless, abrupt edges, compromised apertures, a slit for a headlamp bar, and a cabin that reads as armored denial rather than welcoming space. It certainly is not selling

Well, if those reservations were actually there. What do we know about how this—to me—incomprehensible set of visual and spatial design considerations came to be? My (somewhat informed) guess is this: Manufacturing theory collided with physics, regulation, ergonomics, and trucks-as-tribal-signal—and then lost coherence. Let me expand on that in five parts: First: the exoskeleton thesis—and its costs: Musk said they would build an “exoskeleton,” putting structural duty on ultra-hard, flat stainless panels rather than on a conventional body-on-frame or unibody shell plus cosmetic skin. Philosophically, this promises fewer stamped complex forms, cheaper dies, and a design language that is straight lines and simple bends—conceptually elegant, visually brutalist, and nominally cost‑reducing. But automotive structure isn’t a geometry homework problem, is it? Torsional stiffness; crumple behavior; plus noise, vibration, and harshness will all benefit from curves, variable thicknesses, and energy‑absorbing members. It greatly complicates sealing where flat plates meet at sharp angles. An exoskeleton made of hard stainless complicates controlled deformation in crashes. Early leaks and anayses suggested Tesla struggled with exactly those basics: sealing the body against leaks and noise, poor braking feel and stability, odd handling artifacts (“excessive lateral jerk,” “head‑toss,” and “structural shake”), and a “significant gap to targets” in suspension kinematics. Documents tell of some problem items with “possibly none” as the recommended fix. Thus the form language that supposedly simplifies production can introduce first‑principles problems in how cars behave, sound, and protect. I think that is the heart of the incomprehensibility: the visual philosophy asserts simplicity; the mechanical and human consequences do not. Second: aero, apertures, and the tyranny of triangles: Trucks are bricks; EVs need aero. The Cybertruck’s head‑on and roofline geometries mix sharp overhangs and facets that create separated flow and turbulence. That is defensible if you gain enough by eliminating compound curves in stamping. But the triangle takes back in drag what it saves in tool complexity. Moreover, usable life is doors, sightlines, ingress/exit, and truck-bed usefulness. Severe angles compress door apertures and compromise. You can write a manifesto that trucks should feel armored; users still want to get in and see out. Truck-bed usefulness suffers from structures that are form‑driven rather than use‑driven. Plus the interior aesthetic—flat planes and cold materials—reads “bunker”, not “living room”. The upside of the skateboard possibility is a flat floor and an airy cabin. The Cybertruck’s geometry throws that upside away. Third: regulation and human factors are not optional: The launch prototype famously lacked road‑legal mirrors and had defective. Two generations of crashworthiness passenger-protection have standardized on relying on crumple zones—controlled progressive deformation—to absorb energy before it reaches passengers. A hard, planar, high‑yield stainless surface really wants to stay un-deformed. It thus transmits forces elsewhere, until it yields catastrophically. You could engineer crumple behind the shell. But then the shell’s visual conceit (the “exoskeleton carries structure”) is undermined by hidden conventional members doing the work. The resulting design is conceptually proud and visually defiant. But making it road-ready forced the vehicle back toward the compromises the rest of the industry already solved. Anti‑humanistic is a mood plus: it means that the object also malfunctions, resisting the need to accommode bodies, senses, and rules. Fourth: signaling and the market segment: Pickups in America used to be tools. Now they are culture. Makers build them to signal dominance, capability, tribe. Tesla attempted to create a new tribe. Call them: the techno‑sovereign Mad Max post‑apocalyptic. The visuals—the “PlayStation 1 graphics” polygonal look—are deliberate. If a brand can sell a new identity, the form can be forgiven many sins. But the truck category’s tribal mojo is based on at least the appearance of successful utility. It has to be stable or at least look stable when you watch it tow something: that stability depends on suspension geometry and mass distribution. It has to carry things, or at least let you see that others are using it to carry things. And there have to be at least advertisements in which you see it successfully going off‑road. The Cybertruck had to satisfy both the identity market (it looks like nothing else) and the perceived utility market (you can watch someone using it to work like a useful truck). The visual stance promised invincibility; the spatial and mechanical reality delivered trade‑offs unpalatable to both tribes. Fifth: the capability fail: No comfort advantages, low range, and little ability to be a useful truck. Sixth: platform economics versus bespoke sculpture: EV winners are going to amortize battery, drive units, and crash structures across multiple bodies—SUV, van, hatch, pickup—extracting scale while tailoring top‑hats to taste. This is the oldest of the GM lessons: Chevy parts produced at the largest and most efficient scale possible used in every product line. The Cybertruck is, by intent, non‑transferable aesthetic capital. Its geometry doesn’t generalize; its material choice (stainless) isn’t a flexible mass‑market strategy; its structural conceit (exoskeleton) is ill‑matched to regulatory and NVH needs. That makes it an economic orphan. If the truck had been a triumph, you could justify the bespoke line. But as demand flattened and inventory rose, the inability to spin the “triangle and steel” recipe into other profitable shapes left Tesla carrying a design theory cost without a platform dividend. In the long arc, EV packaging freedom creates options; the Cybertruck chose a visual constraint that foreclosed many. What, then, is “incomprehensible” about the Cybertruck’s design? Not that it looks strange—strange can be brilliant—but that its visual philosophy repeatedly works against the spatial and mechanical benefits the EV skateboard grants, while incurring extra costs in sealing, NVH, crash behavior, aero, and utility. It denies the human: harder to enter, harder to see out of, less warm. It denies the regulator until forced to comply. It denies the truck’s core use-cases unless you buy the aesthetic as the use-case. I guess the generous reading is that Musk tried to compress a conceptual sculpture—flat plates; stainless authenticity; anti‑ornamental modernism—into a regulated, mass‑manufactured, high‑utility platform. The sculpture won the silhouette; the platform won the compromises; the buyer lost the plot. To summarize: The EV era’s gift is generous interior space and civilized dynamics. The Cybertruck mostly looks like a refusal to accept that gift. References:

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…#what-happened-with-elon-musk-and-the-cybertruck-anywayPlease forward the email & otherwise share it to everyone you think would appreciate it… |

What Happened with Elon Musk & the "CyberTruck", Anyway?

Tuesday, 7 October 2025

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment