This is Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality—my attempt to make myself, and all of you out there in SubStackLand, smarter by writing where I have Value Above Replacement and shutting up where I do not… What Happened with Elon Musk & the "CyberTruck", Anyway?EV freedom vs. bunker aesthetics: how the Cybertruck squandered the skateboard, and misfired as its stainless shell met actual materials-science physics. A bold silhouette, a brittle reality: the...EV freedom vs. bunker aesthetics: how the Cybertruck squandered the skateboard, and misfired as its stainless shell met actual materials-science physics. A bold silhouette, a brittle reality: the CyberTruck as anti-humanist sculpture…EV skateboards enable airy, efficient cabins, yet the Cybertruck chose bunker aesthetics and hostile apertures. It denies utility, comfort, and scale economics. Its success depended on creating a new tribe—call them the lovers of while demanding a new tribe to forgive the trade-offs. But it turned out that the original Tesla market segment of rich techbros who wanted to pledge allegiance to an electric and green future did not want the techno‑sovereign Mad Max post‑apocalyptic vibe of the CyberTruck, and with Musk’s kleptofascist political turn it turned out that the market for Dukes-of-Hazzard-themed CyberTrucks was very limited. And now we are approaching the denouement:

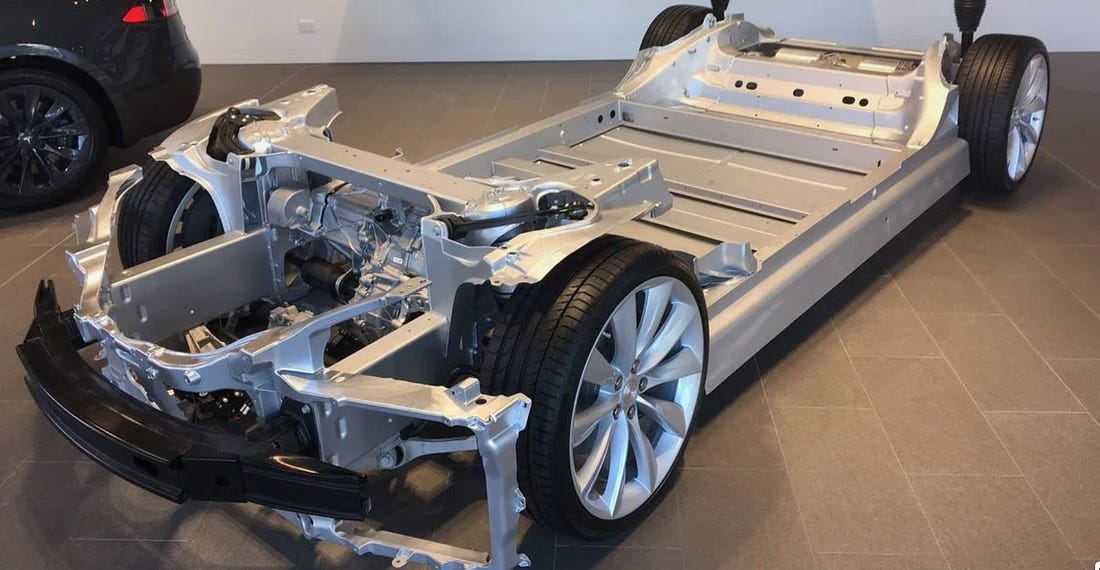

An electric vehicle is—or can be—a skateboard: a flat, self-contained chassis that houses the battery, motors, thermal management, crash structures, and control electronics, upon which you bolt a “top‑hat” of nearly any shape. That modularity has mattered for both engineering economics and product variety since the early 2000s, when GM’s AUTOnomy/Hy‑Wire experiments showed proof that propulsion and energy storage belong in the floor. The modern execution is everywhere: Tesla S/3/X/Y, Rivian’s quad‑motor “adventure”, Volkswagen’s MEB for the ID. family: Consider our VW ID.BUZZ: Take the skateboard’s flat floor and low center of gravity, then drop a faithful 1960s MicroBus “top‑hat” on it: Suddenly you have: maximal cubic volume for people and stuff, easy ingress and egress, and sightlines that feel more living room than cockpit. It’s a nostalgia aesthetic doing real work: The retro form factor isn’t just charming. It’s packaging‑efficient. And in Berkeley it doubles as social signaling: less “tech‑bro brutalism,” more “community‑minded practicality”, plus it makes us the object of great envy on the part of all of our 70‑something onetime-hippie or hippie-want-to-have-been neighbors. So why, given all that design freedom, would you sculpt a vehicle into a maze of cramped corners and overhangs—functionally hostile, aerodynamically mediocre—and then finish it with the visual vocabulary of a dumpster? Most EV makers, and the earlier Tesla, used that freedom to produce swoopy forms with good aero, pleasant sightlines, and cabins that feel like rooms, not bunkers. Tesla, with the Cybertruck, chose instead a low-resolution triangle: severe planar stainless, abrupt edges, compromised apertures, a slit for a headlamp bar, and a cabin that reads as armored denial rather than welcoming space. It certainly is not selling

Well, if those reservations were actually there. What do we know about how this—to me—incomprehensible set of visual and spatial design considerations came to be? My (somewhat informed) guess is this: Manufacturing theory collided with physics, regulation, ergonomics, and trucks-as-tribal-signal—and then lost coherence. Let me expand on that in five parts:... Keep reading with a 7-day free trialSubscribe to DeLong's Grasping Reality: Economy in the 2000s & Before to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives. A subscription gets you:

|

What Happened with Elon Musk & the "CyberTruck", Anyway?

Tuesday, 7 October 2025

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment