This is Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality—my attempt to make myself, and all of you out there in SubStackLand, smarter by writing where I have Value Above Replacement and shutting up where I do not… The Streaming Wars Were Just Plain WeirdNetflix climbs to the top of the streaming-success mountain only to see a much bigger mountain in front of it still to climb: The streaming wars were always going to end like this as the cable...Netflix climbs to the top of the streaming-success mountain only to see a much bigger mountain in front of it still to climb: The streaming wars were always going to end like this as the cable bundles unraveled. The studios thought they were building software platforms; what they actually built were loss-making bundles with worse economics than cable. A predictable hunt for scale, financed by free money, ended with the old studios crawling back to the aggregator they had once sworn they would escape. Netflix didn’t out‑innovate Hollywood so much as outlast a series of balance sheets mispriced on the expectation of a permanent zero‑rate world. Now, however Netflix faces the true apex predator of the digital attention mediascape, in the hydra challenges of Sora and ninety other kinds of slop gathering in their lair in Mountain View, CA…The weirdest thing about the “streaming wars” is that, both now ex post and back then ex ante, they look so utterly predictable. Netflix rode a first‑mover advantage and very cheap capital to global scale. The legacy studios panicked at the sight of their licensing cash cow defecting to the rival camp. Everyone decided that the future of television is a loss‑making “growth” story dressed up in venture‑capital drag; too much money chased too few paying eyeballs. Eventually Wall Street discovered the P&L, demands free cash flow, and the brave new world of “everything on demand, ad‑free, at $6.99 a month” collapses back into bundles, ads, consolidation, and a frantic attempt to get back to the low-cost shared-monopoly of the cable bundle. Meanwhile, YouTube quietly became the largest “television network” on earth. But beforehand, from the inside, it did not feel the way it looked from the outside. It felt like a gold rush. And in what people imagine is a gold rush, everyone convinces themselves that they are Levi Strauss. Hollywood majors had lived very comfortably on a particular stack of rents: windowed distribution, geographic price discrimination, cable carriage fees, and, in the background, the enormous quasi‑monopoly profits of the American pay‑TV cable bundle. Netflix’s streaming innovation—take the back catalogs that studios had been dribbling out on cable channels and DVDs, wrap them in a snappy interface, and sell the whole thing as “all you can eat” for the price of a matinee ticket—looked, to the studios, like easy money. They could license library content they had already amortized, get a big check. And they did not have to worry about cannibalization because, after all, this was just “non‑linear” complementing their linear windows. Then, sometime between “House of Cards” and Disney’s 2019 investor day, the penny dropped. Netflix was not a quirky ancillary outlet. It was rebuilding the bundle in its own image, using everyone else’s content as kindling. The studios’ fear wasn’t irrational. If you license your crown jewels to a player whose only moat is subscription scale and whose recommendation algorithm treats your brand as raw material, you are in the business of manufacturing your own undertaker. So each studio pulled content back from Netflix and tried to become Netflix. They convinced themselves that the streaming P&L looked like software: high fixed costs, near‑zero marginal cost, global addressable market. All you had to do was endure a few years of red ink “building scale”, reassure Wall Street that losses were really “investment”, and wind up in half a decade in the Glorious Future of the subscription annuity machine. And thus the weirdness began. Legacy entertainment companies are not actually software firms. They have unions, backlots, theatrical windows, affiliates, and debt structures optimized for the old cable bundle. Their executives had spent decades optimizing a very particular industrial equilibrium: milk linear television and theatrical; sprinkle output deals across platforms; use scarcity and staggered release to maintain pricing power. Turning all of that into a single, global, low‑priced streaming product was not just a matter of spinning up an app. It meant cannibalizing their own cash flow while betting that they, and not their rivals, would be one of the three at most services the average household would tolerate paying for. Yet in the late 2010s everyone piled in:

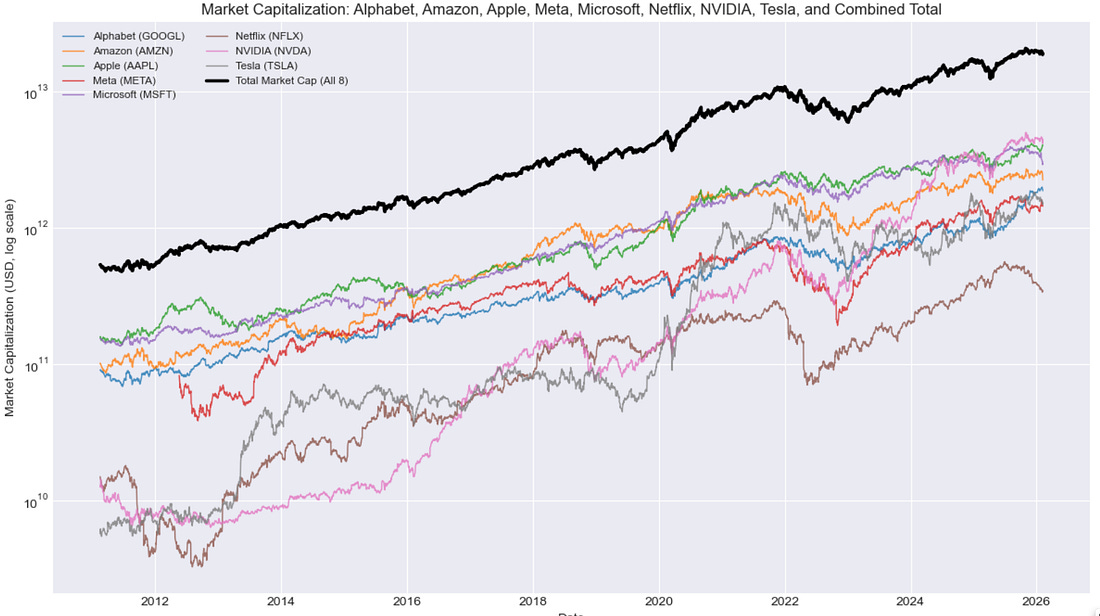

They all had the same pitch deck: “flywheel” slides about original content driving subscribers, data driving smarter commissioning, and global scale delivering operating leverage. They all priced low to gain subs. They all promised the Street that they, too, would someday have the valuation multiple of Netflix. Why did they all think they could make money starting streaming services to compete with Netflix? Because they thought they saw a classic platform play. Because they were terrified of dependence on a rival. Because their investors demanded a growth narrative. Why were they disappointed? Because consumers turned out to be price‑sensitive. Because consumers were not sticky to the studio. Because the cost curves of high‑end video do not look like the cost curves of software. Because interest rates eventually went up. And so disappointment was baked in by arithmetic. Households are finite. Churn is real. Content is expensive. The covid lockdowns provided a one‑off sugar high, but then the world reopened, growth stalled, and the Street’s patience for “we’ll make money next cycle” wore thin. The cost of capital rose. Suddenly those projected hockey‑stick curves were being discounted at something closer to reality. At that point, the studios rediscovered a basic fact: this was always going to be a scale game. To make the economics of streaming work, you either needed a colossal, global subscriber base that could spread your $15‑20 billion content budget over hundreds of millions of paying customers—the Netflix path—or you needed to treat streaming as a complement to some other profit engine: a hardware ecosystem (Apple), a theme park empire (Disney), or a retail and cloud juggernaut (Amazon). What you could not be, indefinitely, with no side business to provide subsidies, was a mid‑sized pure‑play SVOD that depended on $9.99 monthly subscriptions and expensive originals,. Hence now the same studios that had once vowed never again to “rent out” their IP are now happily shoveling old hits back to Netflix because Netflix will actually pay for them. And Wall Street no longer wants direct‑to‑consumer “stories” but near‑term cash flow, and that means licensing back to the very aggregator they created the streaming arms race to escape, so be it. The “streaming war” was not a clash of civilizations. Rather, it was a very costly way to relearn that scale matters and that global subscription platforms are rare. And so Netflix survived, and now it looks like it was won. Netflix had the head start: streaming in 2007, originals in 2013, a decade of building not just a catalog but a global distribution and recommendation machine. It had the right capital story at the right time: in the zero‑interest‑rate world, promising future growth in exchange for present losses was exactly what the market wanted to hear. It had the organizational willingness to behave like a tech company: lots of A/B testing, a focus on product and personalization, and a ruthlessness about sunsetting shows that did not deliver. By the time the studios arrived on the battlefield, Netflix’s trenches were already dug. And why did Netflix survive the competition? Because it got there first. Because it scaled faster. Because it learned to live with advertising instead of defining itself against it. And because the legacy companies, after trying out the role of disruptor, painfully began to rediscover that they were and that, in fact, their only path to possible profitability was to embrace their true identity as suppliers. But the strangest twist is that Netflix is not really the apex predator in the attention economy. YouTube is. If you care about viewing time rather than subscriptions, YouTube is television, and now commands a larger share of total TV viewing in the US than any single subscription streamer with the radically different economic model of user‑generated ad‑supported content free at the point of use. Netflix has to spend on the order of $17 billion a year to fill its shelves; YouTube gets its inventory from millions of creators, compensated via revenue shares and the hope of fame. The old studios fought and lost the last war while the next war began with 10‑minute videos about Minecraft, makeup, politics, and pool cues played on a free, algorithmic video jukebox owned by Google. And why did Netflix survive the sideways rise of YouTube? Well, it may not—at least not as something that is in any sense one of any “FAANG” or “Magnificent Seven”. Right now the market capitalizations of the eight including Netflix are:

Compare to their total of $1.1 trillion in dollars worth half again as much fifteen years ago. NFLX has, however, more than kept pace with the then-tech-supergiants-to-be: back then NFLX was 1% of the total, and today it is 1.7% . (And it would be impolite to ask me what TSLA is doing in this mix.) Now comes Emma Roth to say:

If the Warner Bros.-Netflix merger happens, that is: if Netflix has bribed the Trump family enough and if David and Larry Ellison and Paramount have bribed the Trump family too little and so insurmountable “regulatory” obstacles to the deal do not appear. Then Netflix can profit at pricing levels that other streamers cannot compete at, and they will either have to consolidate further, or throw in the towel and rent their shows out to Netflix at whatever prices it is willing to pay. So what happens next? To help you think this through, I think the most valuable thing you can do right now is go and listen to the very recent Decoder podcast episode in which Nilay Patel interviews Julia Alexander <https://www.theverge.com/podcast/869464/netflix-warner-bros-discovery-deal-paramount-skydance-hollywood-streaming-future>. The most striking moment of it is one that should make Netflix quake in fear. It is Nilay’s “As far as I can tell, every company that has ever bought Warner Bros. has killed itself.” That is: everybody buys Warner as a key step in executing their plan, but, as Mike Tyson once said, “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth” <https://quoteinvestigator.com/2021/08/25/plans-hit/>. The changes in technology and viewer patterns cause the market to punch whoever just bought Warner in the mouth, and they freeze—and then they do not have the money they spent buying Warner to react. Here’s my guess as to what is likely to happen next:... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |

The Streaming Wars Were Just Plain Weird

Sunday, 8 February 2026

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment