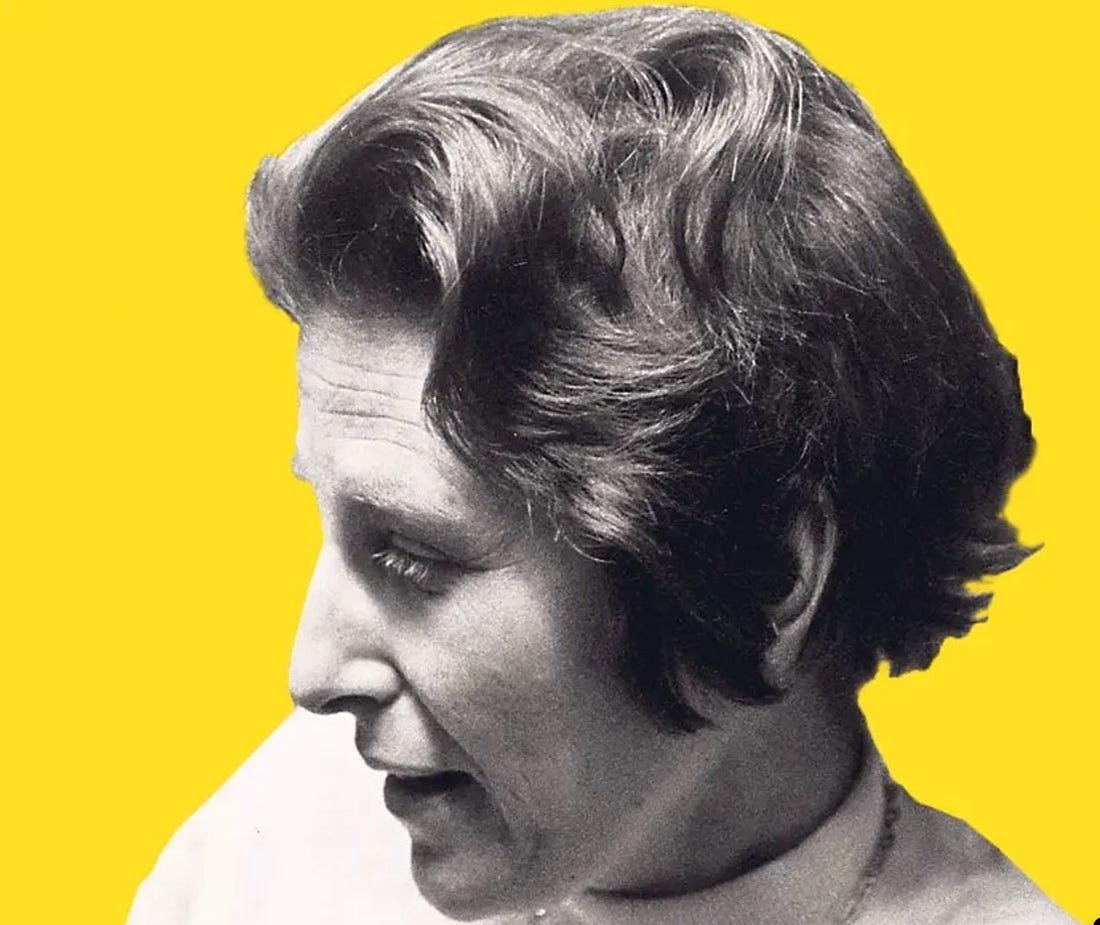

Judith Shklar’s was one of those incredible mid-1900s intellectual lives—not quite at the level of Albert Hirschman’s, but quite close. So many pieces of it are worth excerpting and deeply meditating on. Here is one, on navigating Harvard’s gendered gatekeeping—and rewriting the rules—largely by accident: dependency, ambition, liberal fairness, merit, malice, and making a career in mid‑1900s élite American academia:

It would be naive of me to pretend that I was not asked to give this lecture because I am a woman. There is a considerable interest just now in the careers of women such as I, and it would be almost a breach of contract for me to say nothing about the subject.

But before I begin that part of my story, I must say that at the time when I began my professional life, I did not think of my prospects or my circumstances primarily in terms of gender. There were many other things about me that seemed to me far more significant, and being a woman simply did not cause me much academic grief.

From the first there were teachers and later publishers who went out of their way to help me, not condescendingly, but as a matter of fairness. These were often the sons of the old suffragettes and the remnants of the Progressive Era. I liked them and admired them, though they were a pretty battered and beaten lot, on the whole, by then.

Still they gave me a glimpse of American liberalism at its best.

Moreover, I was not all alone. There were a few other young women in my classes, and those who persevered have all had remarkable careers.

Nevertheless, all was not well.

I had hardly arrived when the wife of one of my teachers asked me bluntly why I wanted to go to graduate school, when I should be promoting my husband’s career and having babies. And with one or two exceptions that was the line most of the departmental wives followed. They took the view that I should attend their sewing circle, itself a ghastly scene in which the wives of the tenured bullied the younger women, who trembled lest they jeopardize their husbands’ future.

I disliked these women, all of them, and simply ignored them.

In retrospect I am horrified at my inability to understand their real situation. I saw only their hostility, not their self-sacrifices. The culture created by these dependent women has largely disappeared, but some of its less agreeable habits still survive. Any hierarchical and competitive society, such as Harvard, is likely to generate a lot of gossip about who is up and who is down. It puts the lower layers in touch with those above them, and it is an avenue for malice and envy to travel up and down the scale.

When I became sufficiently successful to be noticed, I inevitably became the subject of gossip, and oddly I find it extremely objectionable. I detest being verbally served for dinner by academic hostesses, so to speak, and I particularly resent it when my husband and children are made into objects of invasive curiosity and entertainment by them.

These nuisances are surely trivial, and I mention them in order not to sound too loyal to Harvard.

Though perhaps I am, because my experiences have not made me very critical.

Certainly in class and in examinations I was not treated differently than my male fellowstudents. When it came to teaching Harvard undergraduates in sections there was a minor crisis. It was thought wonderful to have me do Radcliffe sections, but men! It had never been done! I said nothing, being far too proud to complain. After a year of dithering my elders decided that this was absurd and I began to teach at Harvard without anyone noticing it at all.

When I graduated I was, much to my own surprise, offered an instructorship in the Government Department. When I asked, how come? I was told that I deserved it and that was that. I did not, however, know whether I wanted it. I had just had our first child and I wanted to stay with him for his first year. That proved acceptable. I rocked the cradle and wrote my first book.

To the extent that I had made any plans for my professional future at all, I saw it in high-class literary journalism. I would have liked to be a literary editor of The Atlantic or some such publication. This was a perfectly realistic ambition and had obvious attractions for a young woman who wanted to raise a family. I was, moreover, sure that I would go on studying and writing about political theory, which was my real calling.

My husband, however, thought that I ought to give the Harvard job a chance. I could quit if I didn’t like it, and I might regret not trying it out at all. So I more or less drifted into a university career, and as I went along there were always male friends telling me what to do and promoting my interests. I did not mind then and I wouldn’t mind now, especially as thinking ahead is not something I do well or often…

No comments:

Post a Comment