This is Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality—my attempt to make myself, and all of you out there in SubStackLand, smarter by writing where I have Value Above Replacement and shutting up where I do not… HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: Yes: Pre-Modern Economies Were Meaningfully "Malthusian" (Which Does Not Mean Incomes Were Stable)Putting this here so I can find it easily. Originally 2023-03-07. Contra Rafael Guthman; or, what a Malthusian economy looks like. Rafael is doing something genuinely interesting and valuable: he...Putting this here so I can find it easily. Originally 2023-03-07. Contra Rafael Guthman; or, what a Malthusian economy looks like. Rafael is doing something genuinely interesting and valuable: he is insisting that the pre‑modern world was not a flat line of misery, and he is right about that. Where he goes wrong is in thinking that this empirical richness is a refutation of “Malthusian” dynamics rather than an illustration of how they actually look in the wild…<https://braddelong.substack.com/p/yes-pre-modern-economies-were-meaningfully> Rafael Guthman Says on the Internet That I Am Wrong!This is, of course, wonderful: a smart and thoughtful person disagreeing with me on the internet. He is, of course, wrong. But now I get to revisit my trains of thought, and explain why he is, in his turn wrong.

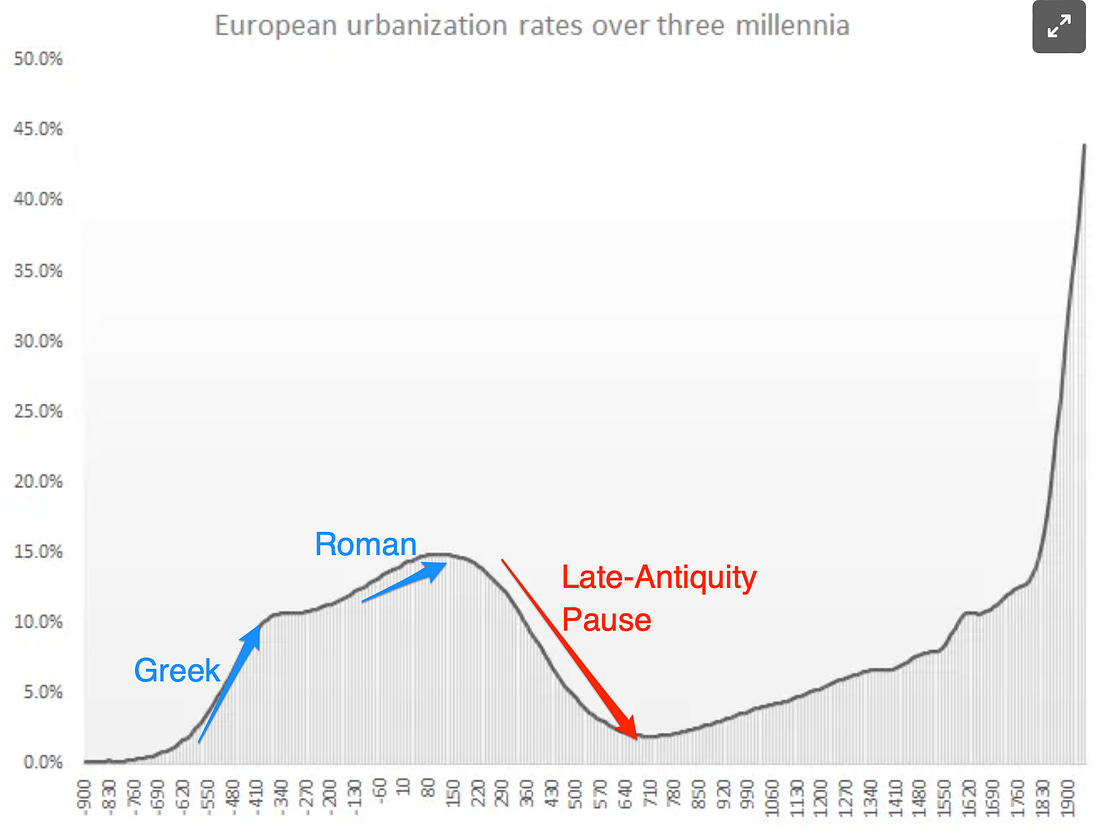

The three cycles are (1) the Bronze Age Near East starting in -3000, followed by the late -1000s civilizational collapse; (2) the Classical and Hellenistic Greece plus Roman efflorescence from -700 to 150, followed by what I politely call the “Late-Antiquity Pause” from 150 to 700; and (3) the long mediæval and early modern ascent, followed by the industrial revolution and modern economic growth breakthrough. The support is (1) the assertion that urbanization—even in cities as small as 5000—is closely correlated sith living standards an productivity levels, and (2) our guesses about the share of Europeans living in cities of 5000 or more: Rafael says:

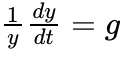

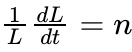

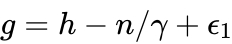

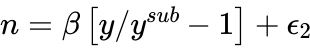

But what would we expect to see if we were, in fact, observing a Malthusian economy? What is a Malthusian economy anyway? I write it down in four equations:     The first and second equations are simply definitions: The first says that we are going to give proportional growth rate of living standards and productivity levels—the proportional growth rate of the output per worker y variable on the left-hand side—a label, and that label will be g, g for growth. The second says that we are going to give the proportional growth rate of population and the labor force L, L for labor, a label, and that label is on the right-hand side and is n, n for numbers. The third and fourth equations are behavioral relationships: The third says that g—the proportional growth rate of living standards and productivity levels—on the left-hand side is equal to the proportional rate of growth h of human ideas about technology, minus the proportional rate of growth of population and the labor force n, with that latter divided by a parameter ɣ—a parameter that tells us how salient ideas about technology are in generating productivity vis-à-vis resource scarcity, plus a random shock term. It is human ingenuity versus resource scarcity. And resource scarcity is made more dire by population increases. The fourth says that the population growth rate variable n on the left-hand side will be such that population will grow if living standards y are above, and shrink if living standards are below, some “subsistence” level y^{sub}. It says that how much population will do so depends on a parameter β—a parameter that tells us how responsive fertility and mortality are to want and deprivation, plus another random shock term. Twice as big a gap between living standards and subsistence will produce twice as fast a population response, with the value of the β parameter calibrating how much. As people get poorer, fertility drops: women become sufficiently skinny that ovulation becomes hit-or-miss. And as people get poorer, mortality rises: it is not just that some people starve to death, it is that the malnourished have compromised immune systems, and malnourished children, especially, are easily carried off by the common cold. This model captures three features of a pre-modern Malthusian economy:

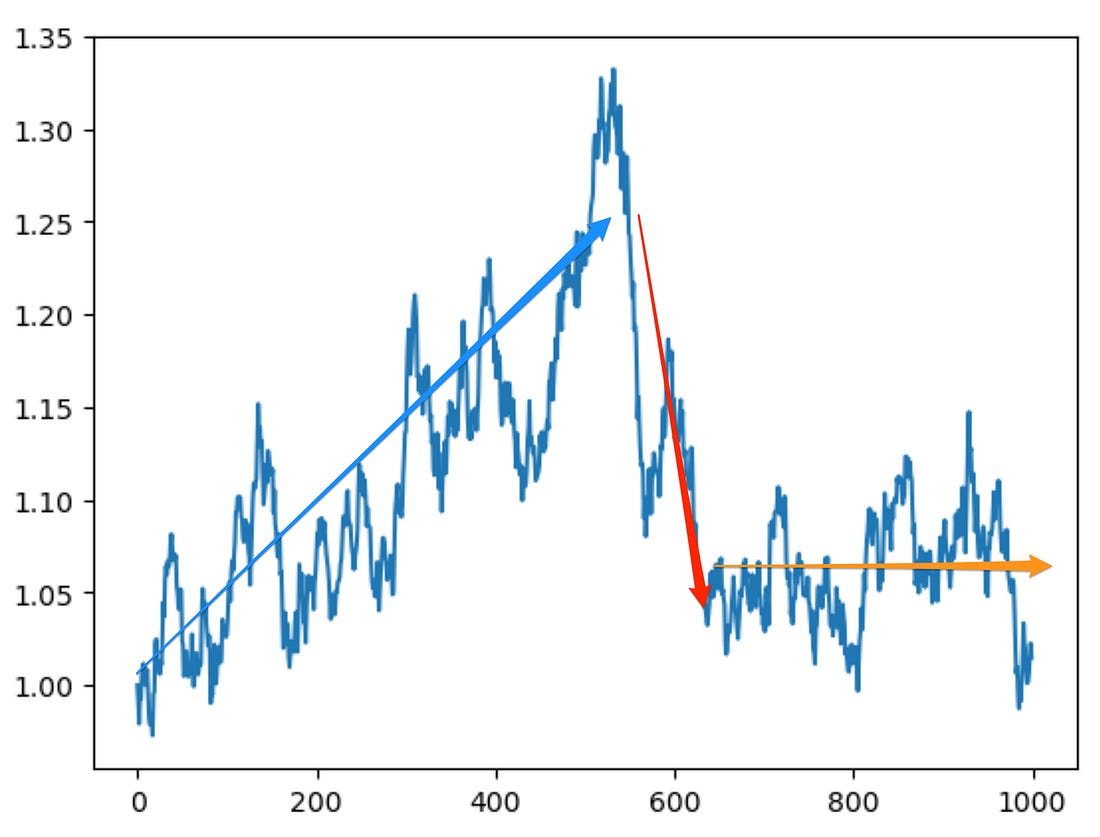

What consequences do those features have? Well, let us set up a toy economy—a simulation—with these features, and only these features, and see how history evolves. Let us set h = 0.0005—5% growth in technology over a century. Let us set β= 0.25—if real living standards are 40% over “subsistence”, population grows at 1% per year, or doubles in three generations. And let us set ɣ = 2—ideas about technology are twice as salient as resources in generating productivity. And we also need to add a random term, an ε term, for plagues, bountiful harvests, mild winters in which babies do not die of pneumonia, and all the other non-systematic accidents that affect the growth of population. We do this in Python. Here is our first simulation run: the level of income per capita: We see, in this simulation, a 500-year advance in civilization as measured by living standards, and then a sudden following crash into a dark age. There is then a 400-year period during which little appears to happen. Would Rafael Guthman say of this that there “no evidence of any tendency… to stabilize around a level consistent with the Malthusian model’s ‘subsistence level’”? Would he point to it as strong evidence against the Malthusian economy hypothesis? Quite possibly. I would even say: probably. And yet there it is. There is nothing non-Malthusian going on here. There are no patterns. There are only chance shocks here. We find patterns even where there are no patterns—where there is only the random buffeting of the society by plague and good harvest, with each year’s shocks being independent and unconnected with what was going on before or after in the sense of shocks to the system. Now, actually, I think there is much more going on with the Classical and Hellenistic Greek efflorescences, and with the Roman efflorescence, than just the random chances of plagues and good harvests. But that more is happening than can be captured in my very simple model is not, I think, dispositive. A society can see considerable advances in average living standards and considerable increases in population without thereby ceasing to be Malthusian. A society that acquires a substantial taste for luxuries—for expenditures on things that do not directly contribute to making women more fertile and children more likely to survive—will raise the average standard of living even in a Malthusian economy. So will customs, like late female first marriage or female infanticide, that will have the effect of diminishing reproduction. And the coming of a large commercial trade zone or an imperial peace—something that greatly increases the rewards of investing in tools and infrastructure and other forms of social, public, and private capital—will raise the average standard of living in the short run, and raise population in the long run, but note that it can take up to half a millennium for the long run to arrive. So I regard Rafael’s figure as a striking illustration of how a Malthusian economy does not have to be completely stagnant. We start with four boring equations. We add year by year (and, in more sophisticated models, multi-year) shocks—plagues, good harvests, the coming of an imperial peace. We iterate in Python. We do not get a flat line. We get exactly what Rafael’s eye is drawn to in the data: centuries‑long upswings in income and population, followed by collapses and plateaus in which nothing much seems to happen for a very long time. In such a world, you can and do have:

And yet the basic logic is still Malthusian: the system never breaks free of the feedback by which higher incomes eventually call forth more people and more resource stress. Tastes for luxuries that don’t raise fertility, customs like late marriage or female infanticide, or a large trade zone and imperial peace that make capital investment more rewarding—all of these can raise average incomes substantially inside a Malthusian regime. They can produce exactly the sort of “supercycles” Rafael documents. They do not, by themselves, produce a world in which sustained, compounding gains in living standards for the broad population become the normal condition rather than an episodic exception. Thus Rafael’s figure does not shake my confidence in the proposition that before 1870 the world economy was Malthusian. It does not shake my confidence in that at all.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…##hoisted from the archives-yes-pre-modern-economies-were-meaningfully-malthusian-which-does-not-mean-incomes-were-stable |

HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: Yes: Pre-Modern Economies Were Meaningfully "Malthusian" (Which Does Not Mean Incomes W…

Wednesday, 4 February 2026

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment