This is Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality—my attempt to make myself, and all of you out there in SubStackLand, smarter by writing where I have Value Above Replacement and shutting up where I do not… The False Calm Before Steam: The Index H, Malthus, & the Long Slog, for Growth Was Very Real Before It Became Visible in Average Living StandardsThe cliché says nothing happened before 1800. The data say capability rose steadily—only population swallowed the dividends. Replace vibes with an index: average income × √population. Suddenly...The cliché says nothing happened before 1800. The data say capability rose steadily—only population swallowed the dividends. Replace vibes with an index: average income × √population. Suddenly, Rome, Han, and Bronze-Age workshop floors look like real steps, not “nothing.” If you think progress began with steam, you’re reading per capita and ignoring people. My index of the value of the stock of technological capability H tells a different story: slowly rising competence, finally outrunning the Devil of Malthus…This, eighteen years old, but in my feed via a referral to a link over on a link from one of the bad social-media websites. I remember it. It struck me back then, and it still strikes me now, as not too smart:

I remember Landsburg. Slate gave him a column for a long time—Michael Kinsley thinking he needed to spend more of Microsoft’s money on “provocative” right-wing s***posters. See: SlatePitch. The Slatepitch was never intellectual contrarianism; it was attention arbitrage. Dress up the obvious as “forbidden truth,” or varnish the indefensible as “counterintuitive genius,” and count the clicks while readers burn minutes they’ll never get back. The trick relies on a bait-and-switch: either posit a claim that violates common sense and then filibuster through rhetorical cleverness, or launder a truism as a brave revelation (“we need to admit X”). In both cases, the scarce resource—reader time—is squandered on provocation rather than illumination. Dan Davies (2009) had a nice take on it back in the day <https://crookedtimber.org/2009/10/22/rules-for-contrarians-1-dont-whine-that-is-all/>:

And that applies in spades to Landsburg’s: “modern humans first emerged about 100,000 years ago. For the next 99,800 years or so, nothing happened…” There is, today, pushback:

And:

I would say that there are six things in play here:

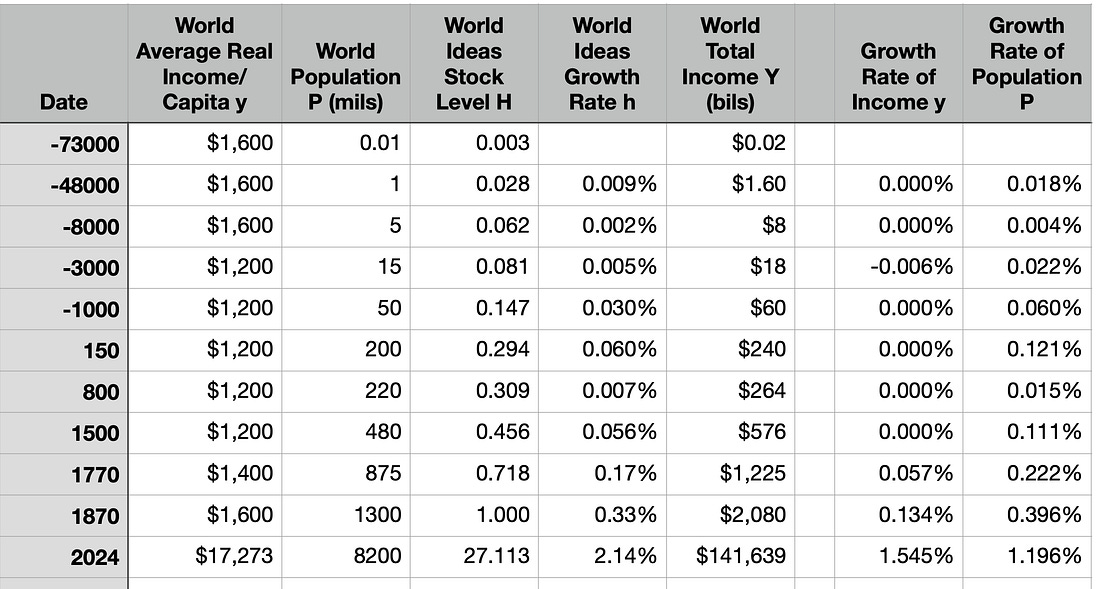

If we are willing to make some truly heroic assumptions, we can deal with (3) and how it is supported by (1) and (2) in a manner that is at least somewhat believable. I, in fact, have the beginnings of a catechism for all this. It is at <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/brad-delongs-history-of-economic>!: Where do you start? I start with a very crude global index of the value of the stock of human technology—useful ideas about manipulating nature and productively organizing humans—that have been discovered, developed, and then deployed-and-diffused throughout the world economy. How do you construct this index? I calculate it as the average worldwide level of income per capita, times the square root of population. Why do you set the technology level proportional to the level of average output per capita? That is just a normalization: it makes it easy to interpret—double the technology level, and you double the average income per capita level the world’s resources can support at a fixed population. Why the square root of population? The square-root recognizes that there is resource scarcity—hence generating income for more people is burdensome, and so the technology level is not simply average output per capita—but also that each mouth comes with two eyes, two arms, and a brain, so that labor is productive—hence total world product is not the technology level either. “Square-root” is a balance. Would you die on the hill that it is square-root, rather than some other power between 0 (which gives average income per capita) or 1 (which gives total world product) multiplying population? No. But do you have a better idea? How about things like changing capital intensity as drivers of economic growth? Even if Solow (1956, 1957) had not scotched that as a dominant factor, I believe that the capital intensity of the average human economy—its capital stock/annual output ratio—has been pretty close to three since shortly after the invention of agriculture. Differences in capital intensity do matter in comparing the relative prosperity levels of different societies at any point in time, but I do not see them as playing any significant role over the long term. What do your guesses—I won’t call them numbers—then show, in terms of the annual average proportional growth rates of technology deployed-and-diffused, worldwide? Roughly:

Basically, growth very slow for millennia—visible only in la longue durée—then growth visible over a human lifetime, barely, after 1500; growth substantial over a human lifetime after 1770; and then growth so that humanity’s technological prowess doubles every generation after 1870. What do your guesses show, in terms of the levels of technology deployed-and-diffused, worldwide? Roughly:

What does this measure tell us about when the big, important quantitative change in the course of human economic growth came? It tells us that the big leap upward in economic growth—the bit watershed boundary-crossing—comes in 1870, when the global rate of technological progress jumps up more or less discontinuously from an average proportional growth rate of 0.45% per year to a rate of at least 2.1% per year. The proportional jump from 1870 to 2020 is larger than the proportional jump from -6000 to 1870. Surely the jump from 1 to more than 20 deserves some intermediate steps? I am playing with:

with each “mode of production” marking a rough doubling of the technology level. If you believe that “the hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist”, then the list above are what you would like to mark and reference: not any of this “asian-ancient-feudal-capitalist-socialist” stuff. Do you really think that the technological-underpinning base and the corresponding superstructures of human society really stayed the same in any meaningful sense from 200 to 1500? No. I take the point that back in the Before Times smaller quantitative changes in the level of productivity had larger qualitative effects on how societies were run—that smaller changes in the forces- and relations-of-production carried with them bigger effects on the superstructure, at least in the long run If, before 1500 we move to dividing history up into “modes of production” by marking an age difference as a roughly √2-ing in our valuation of the stock of deployed-and-diffused “technology”:

Or, in convenient tabular form: But that still leaves us with (4), (5), (6): luxuries—which I define as things and processes you could not have possessed, utilized or experienced beforehand; cultural goods of all kinds; and then there are the negative bidders—those who do not make you offers of good things to induce coöperation, but rather make Don Vito Corleone-like offers that you cannot refuse. And I have not yet proven smart enough to come up with even a semi-defensible way of producing even a rough quantitative guess of the value—or disvalue—of those three. But they are key to answering the original question. No. It is not the case that nothing interesting happened. References:

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…#enlarging-the-scope-of-human-empire |

The False Calm Before Steam: The Index H, Malthus, & the Long Slog, for Growth Was Very Real Before It Became Visi…

Tuesday, 11 November 2025

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment