One major reason AI adoption stalls? Training. (Sponsored)AI implementation often goes sideways due to unclear goals and a lack of a clear framework. This AI Training Checklist from You.com pinpoints common pitfalls and guides you to build a capable, confident team that can make the most out of your AI investment. What you’ll get:

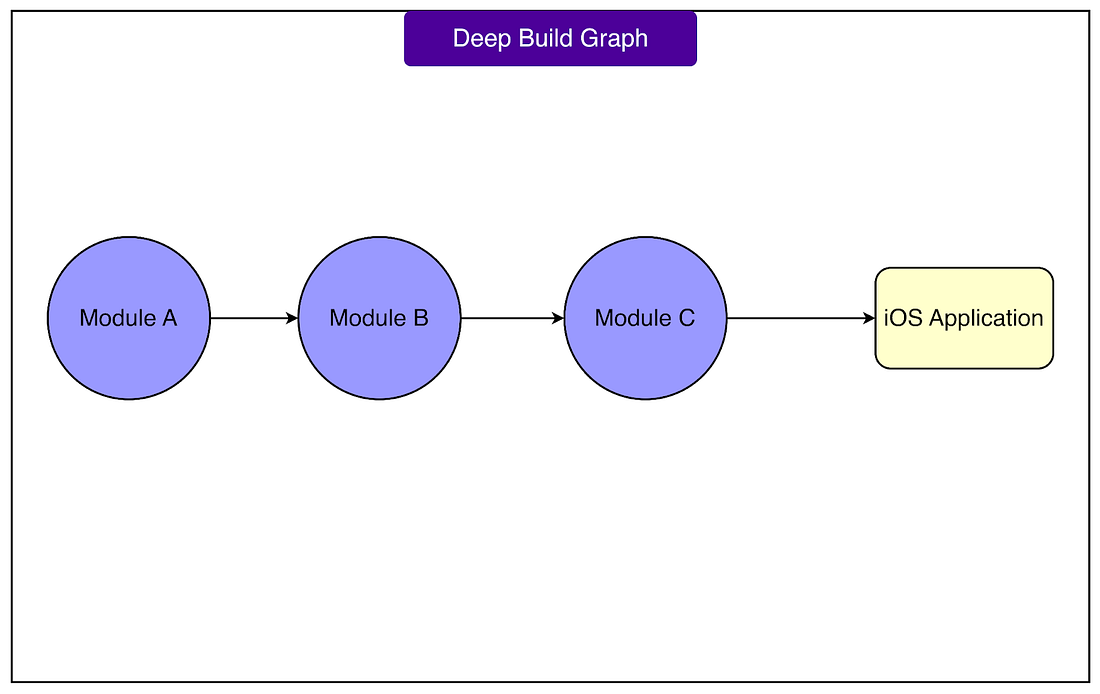

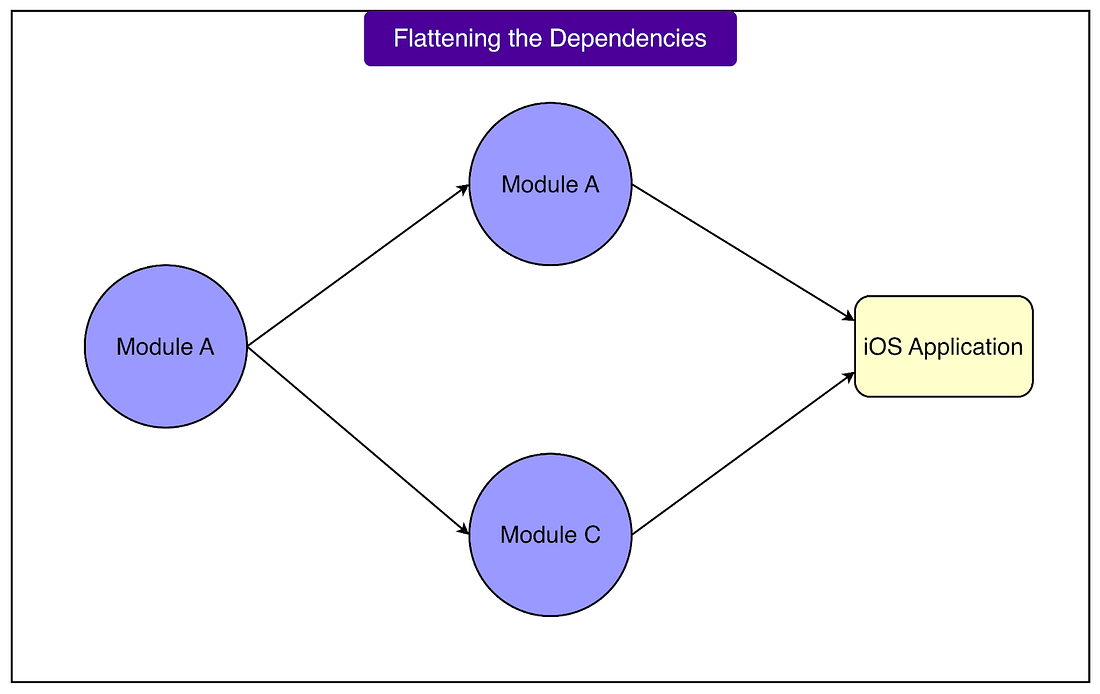

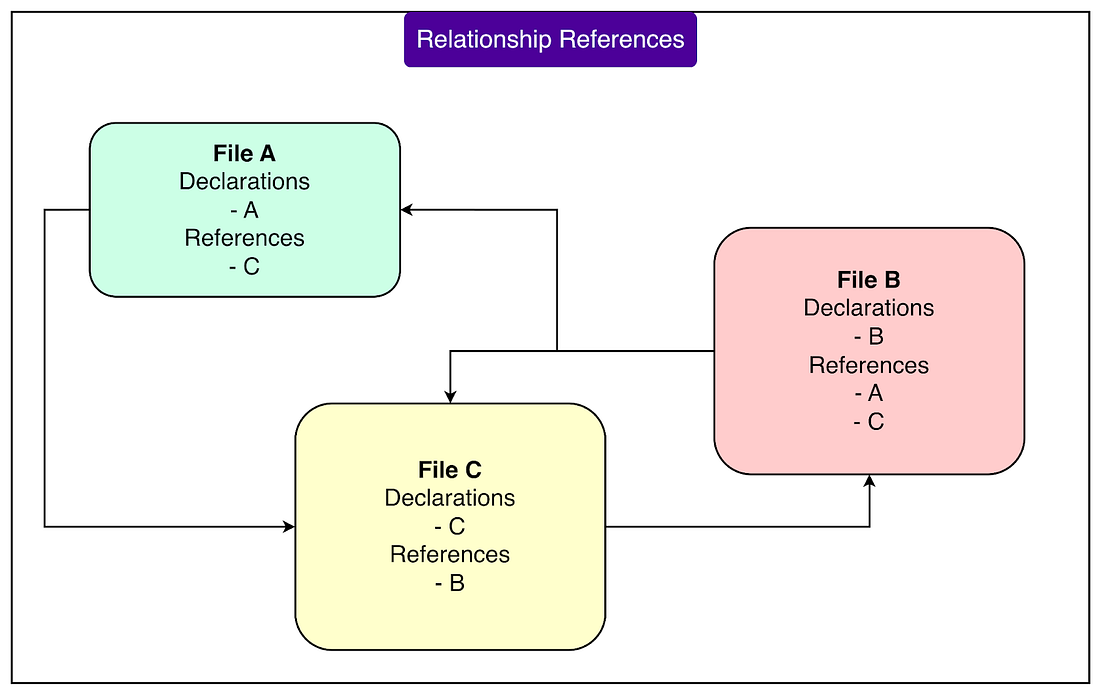

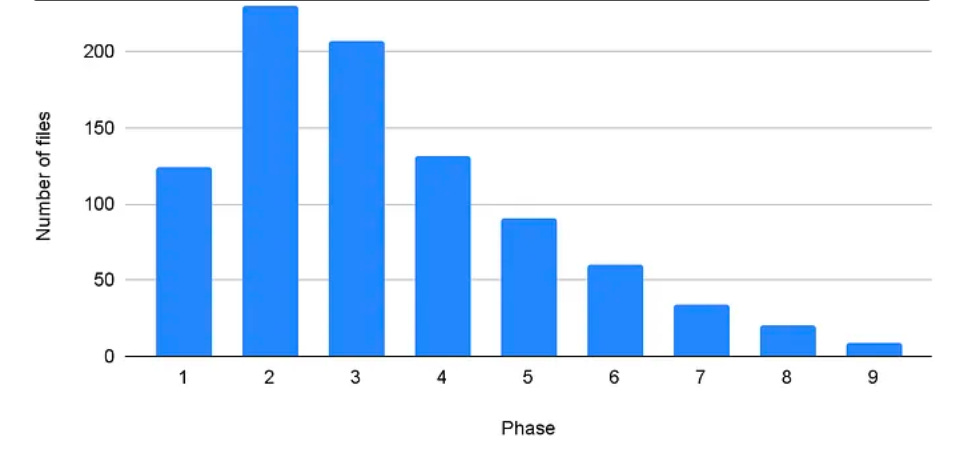

Set your AI initiatives on the right track. Disclaimer: The details in this post have been derived from the details shared online by the Tinder Engineering Team. All credit for the technical details goes to the Tinder Engineering Team. The links to the original articles and sources are present in the references section at the end of the post. We’ve attempted to analyze the details and provide our input about them. If you find any inaccuracies or omissions, please leave a comment, and we will do our best to fix them. Tinder’s iOS app may look simple to its millions of users, but behind that smooth experience lies a complex codebase that must evolve quickly without breaking. Over time, as Tinder kept adding new features, its iOS codebase turned into a monolith. In other words, it became a single, massive block of code where nearly every component was intertwined with others. At first, this kind of structure is convenient. Developers can make changes in one place, and everything compiles together. However, as the app grew, the monolith became a bottleneck. Even small code changes required lengthy builds and extensive testing because everything was connected. Ownership boundaries became blurred: when so many teams touched the same code, it was hard to know who was responsible for what. Over time, making progress felt risky because each update could easily break something unexpected. The root of the problem lies in how iOS applications are built. Ultimately, an iOS app compiles into a single binary artifact, meaning all modules and targets must come together in one final build. In Tinder’s case, deep inter-dependencies between those targets stretched what engineers call the critical path, which is the longest chain of dependent tasks that determines how long a build takes. Since so many components are dependent on each other, Tinder’s build system could not take full advantage of modern multi-core machines. See the diagram below: In simple terms, the system could not build parts of the app in parallel, forcing long waits and limiting developer productivity. The engineering team’s goal was clear: flatten the build graph. This means simplifying and reorganizing the dependency structure so that more components can compile independently. By shortening the critical path and increasing parallelism, Tinder hoped to dramatically reduce build times and restore agility to its development workflow. See the diagram below that tries to demonstrate this concept: In this article, we take a detailed look at how Tinder tackled the challenge of decomposing its monolith and the challenges it faced. Strategy: Modularizing with Compiler-Driven PlanningAfter identifying the core issue with the monolith, Tinder needed a methodical way to separate its massive iOS codebase into smaller, more manageable parts. Trying to do this by hand would have been extremely time-consuming and error-prone. Every file in the app was connected to many others, so removing one piece without understanding the full picture could easily break something else. To avoid this, the Tinder engineering team decided to use the Swift Compiler that already understood how everything in the codebase was connected. Each time an iOS app is built, the compiler analyzes every file, keeping track of which files define certain functions or classes and which other files use them. These relationships are known as declarations and references. For example, if File A defines a class and File B uses that class, the compiler knows there is a dependency from B to A. In simple terms, the compiler already has a map of how different parts of the app talk to each other. Tinder realized this built-in knowledge could be used as a blueprint for modularization. By extracting these declarations and reference relationships, the team could build a dependency graph. This is a type of network diagram that visually represents how code files depend on each other. In this graph, each file in the app becomes a node, and each connection or dependency becomes a link (often called an edge). If File A imports something from File B, then a link is drawn from A to B. This graph gave Tinder a clear and accurate picture of the monolith’s structure. Instead of relying on guesswork, they could now see which parts of the code were tightly coupled and which could safely be separated into independent modules. Execution: Phased Leaf-to-Root ExtractionAfter building the dependency graph, Tinder needed a way to separate the monolith without breaking the app. The graph made it clear which files were independent and which were deeply connected to others. To make progress safely, the Tinder engineering team divided the work into phases. In each phase, they moved a group of files that had the fewest dependencies. These files were known as leaf nodes in the dependency graph. A leaf node is a file that no other files rely on, which makes it much easier to move without disrupting other parts of the system. Starting with these leaf nodes helped the team limit the blast radius, which means reducing the potential side effects of each change. Since these files were less connected, moving them first carried a lower risk of introducing build errors or breaking functionality. This approach also simplified code reviews, because each phase affected only a small and manageable part of the codebase. Once one phase was complete and verified to build correctly, Tinder moved on to the next set of files. Each successful phase made the monolith smaller and cleaner, allowing the next steps to be faster. Over time, this created a clear sense of progress, with the app continuously improving rather than waiting for a big final milestone. By the time they reached the fourth phase, the Tinder team had already completed more than half of the entire decomposition work. This showed that the strategy naturally tackled the simpler and more independent files first, leaving the more complex, interdependent ones for later. What Moving a File Actually MeansBreaking a monolith into smaller modules may sound straightforward, but each “move” in the process has a ripple effect across the rest of the codebase. When the Tinder engineering team moved a file from the monolith into a new subtarget (which is essentially a separate Swift module), several adjustments had to be made to ensure the app still built and functioned correctly. The process usually requires four main types of updates:

In practice, moving a single file often required changes to several others. On average, each file extraction involved edits to about fifteen different files across the codebase. This might include fixing imports, updating dependencies, adjusting access levels, or modifying initialization code. While the automation tools handled much of this mechanical work, engineers still needed to review every change to ensure that the refactoring preserved behavior and followed coding standards. The Role of AutomationBreaking down a large monolith by hand is not only slow but also highly error-prone. For Tinder, with thousands of interconnected files, doing this work manually would have been nearly impossible within a reasonable timeframe. Each time a file was moved, engineers would have needed to rebuild the app to check for new compile errors, fix those issues, and rebuild again. The number of required builds would have grown rapidly as more files were moved, creating what engineers call a quadratic growth problem, in which the effort increases much faster than the number of files being processed. To overcome this, the Tinder engineering team invested heavily in automation. They built tools that could perform the extraction process automatically, following the dependency graph that had already been created. These tools could:

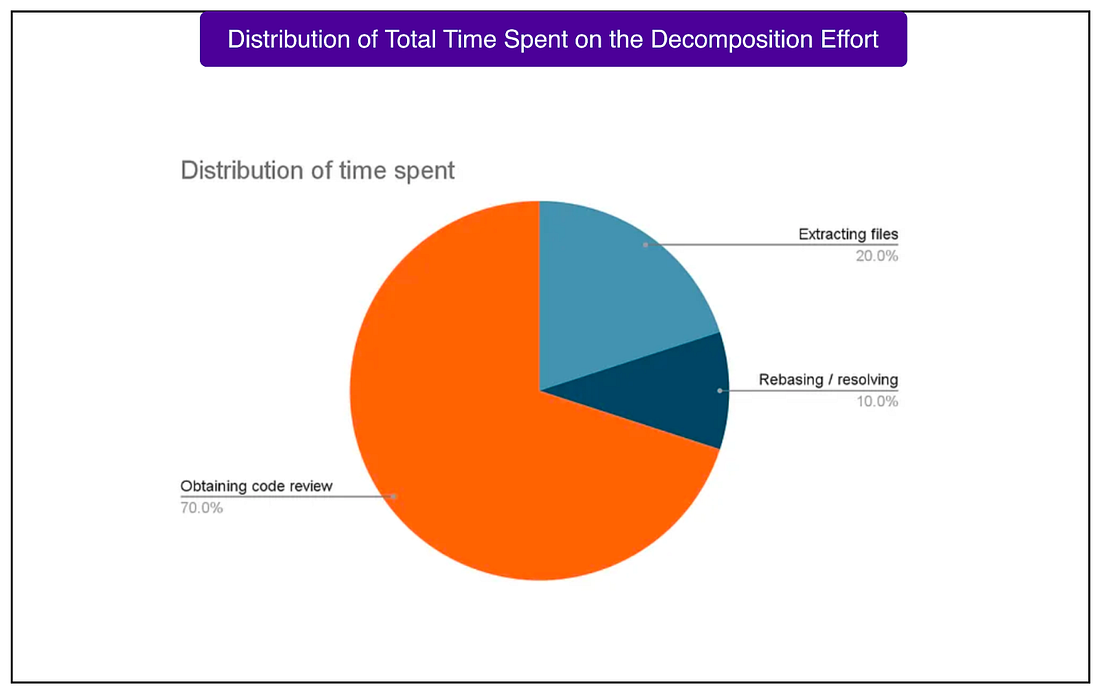

This automation completely changed the timeline of the project. Tinder was able to fully decompose its iOS monolith in less than six months, whereas doing it manually was estimated to take around twelve years. The graph below shows the distribution of time spent on the decomposition effort. The tools transformed what would have been a slow, iterative process into one that operated almost in constant time per phase, meaning each phase took roughly the same amount of effort regardless of its size. ConclusionTinder’s journey from a massive iOS monolith to a modular, maintainable architecture is one of the most striking examples of how thoughtful engineering, automation, and discipline can transform development speed and reliability at scale. By relying on the compiler’s own knowledge to map dependencies, Tinder created a scientific, repeatable process for breaking the monolith apart without risking stability. The results were remarkable.

This change went beyond technology and tools. It created a cultural shift. Engineers now had fewer places to hide quick fixes or shortcuts, and higher standards of modularity, clarity, and ownership became the new normal across the team. For other engineering organizations, Tinder’s experience offers several practical lessons.

References: SPONSOR USGet your product in front of more than 1,000,000 tech professionals. Our newsletter puts your products and services directly in front of an audience that matters - hundreds of thousands of engineering leaders and senior engineers - who have influence over significant tech decisions and big purchases. Space Fills Up Fast - Reserve Today Ad spots typically sell out about 4 weeks in advance. To ensure your ad reaches this influential audience, reserve your space now by emailing sponsorship@bytebytego.com. |

How Tinder Decomposed Its iOS Monolith App Handling 70M Users

Wednesday, 12 November 2025

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment